A celebration of community, living art, and the spirit of bonsai

What an awesome turnout: We estimate that more than 8,000 people joined the Potomac Bonsai Association Festival and World Bonsai Day!

We were thrilled to support PBA as they hosted yet another incredible annual festival. All weekend long, the grounds of the U.S. National Arboretum buzzed with activity, joy, and curiosity. Guests explored the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum, watched awe-inspiring bonsai demonstrations, sipped tea in honor of the Yamaki Pine, participated in hands-on workshops, browsed vendors, found their next bonsai project... and celebrated the art of bonsai together.

As Museum Curator Michael James reflected, the scale and spirit of the event was inspiring. "It was amazing to see the Museum honored by the presence of thousands of visitors from all walks of life," he said. "World Bonsai Day gave us a chance to show how deeply this art form connects people across cultures and generations."

L to R: Aaron Stratten, past president of the Potomac Bonsai Association; Ambassador James Zumwalt, Chairman, Japan-America Society; Ambassador Shigeo Yamada, the Ambassador of Japan; Dr. Richard Olsen, Center Director of the U.S. National Arboretum; Michael James, Curator, National Bonsai & Penjing Museum; Ben de Guzman, Director, Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs

This year we celebrated the 400th anniversary of the Yamaki Pine, also known as the Peace Tree, which stands as a powerful symbol of resilience, peace, and friendship. We marked the occasion with a formal tea toast led by Dr. Richard Olsen, Center Director of the U.S. National Arboretum, and Ambassador Shigeo Yamada, the Ambassador of Japan. This meaningful recognition added a moment of elegance and quiet reflection to a busy, joy-filled day. We are grateful for the specialty Japanese tea service provided by local DC shop Teaism.

L to R: Dr. Richard Olsen, Center Director of the U.S. National Arboretum; Le Ann Duling, President, Potomac Bonsai Association; Ambassador Shigeo Yamada, the Ambassador of Japan; Ambassador James Zumwalt, Chairman, Japan-America Society; Michael James, Curator, National Bonsai & Penjing Museum; Ben de Guzman, Director, Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs

Alongside Dr. Olsen and the Ambassador, we were honored to welcome a remarkable group of speakers and special guests whose presence elevated the spirit and significance of the event:

Ambassador James Zumwalt, Chairman, Japan-America Society

Ben de Guzman, Director, Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs

Le Ann Duling, President, Potomac Bonsai Association

Aaron Stratten, Immediate Past President, Potomac Bonsai Association

Michael James, Curator, National Bonsai & Penjing Museum

We are deeply grateful to them for joining us this year to share their thoughtful reflections on the art and practice of bonsai around the world.

Aaron Stratten and expert guest artist Andrew Robson of Rakuyo Bonsai

Guy Guidry of NOLA Bonsai

The weekend featured engaging, expert-led workshops that drew large, enthusiastic crowds. Our special guest artists, Guy Guidry and Andrew Robson, brought decades of experience and a passion for sharing the art of bonsai. Guidry, known for his bold, expressive styling, demonstrated dramatic transformations that captivated onlookers. Robson, a rising leader in American bonsai, focused on naturalistic approaches to deciduous trees, blending tradition with innovation. Attendees learned both foundational skills and advanced techniques, and many walked away with fresh inspiration and new perspectives.

Sandra Moore reads from her book about the Yamaki Pine.

Sandra Moore, author of The Peace Tree from Hiroshima, joined us as well, sharing the story of the Yamaki Pine with families and young visitors. Her engaging presence and thoughtful readings helped connect the history of this remarkable tree to new generations, reinforcing the themes of peace, resilience, and cross-cultural friendship at the heart of World Bonsai Day.

Museum Volunteer and Docent Phillip Merrit

This festival simply wouldn’t be possible without the dedicated volunteers from PBA, who showed up in full force. Members from Brookside Bonsai Society, Maryland Bonsai Association, Northern Virginia Bonsai Society, and Richmond Bonsai Society helped make the entire weekend run smoothly—with visitor guidance, knowledgeable advice, and hands-on event support.

We also welcomed friends from Baltimore Bonsai Club, the Potomac Viewing Stone Group, and even a full busload of members from the Pennsylvania Bonsai Society, one of the oldest bonsai organizations in the United States. We are so appreciative that they made the trip to celebrate with us! Dan Angelucci and Ross Campbell from the National Bonsai Foundation’s Board of Directors were also in attendance, and we're grateful for their leadership.

A family enjoys World Bonsai Day at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum.

Le Ann Duling, President of PBA, noted that everyone went above and beyond, highlighting how vital our regional clubs and members are to making this festival possible. "Everyone did more than their jobs," she said. "This was a powerful reminder of the strength of our community—and how much we can accomplish when PBA clubs come together."

Grillmaster BBQ serves visitors at World Bonsai Day.

A heartfelt thank you to the food trucks that kept our guests fueled and smiling throughout the weekend: GrillMaster BBQ, Taco Dirty to Me, DC Slices, Blossom Bakery, and Captain Cookie. Their presence helped make the day deliciously memorable.

Workshop participants at World Bonsai Day

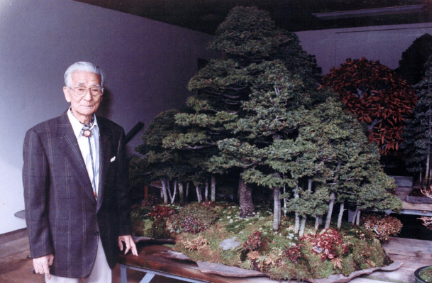

World Bonsai Day reminds us that bonsai is more than an art form—it’s a living tradition that brings people together across generations and cultures. The day was founded in honor of bonsai master Saburo Kato, who taught that bonsai no kokoro, or the spirit of bonsai, is rooted in peace, respect, and shared connection. The PBA Festival showed that this spirit is alive and well.

Thank you to the honored guests, expert artists, dedicated volunteers, helpful partners, and curious visitors who made the weekend so unforgettable! We’re honored to celebrate the beauty, tradition, and future of bonsai with all of you.